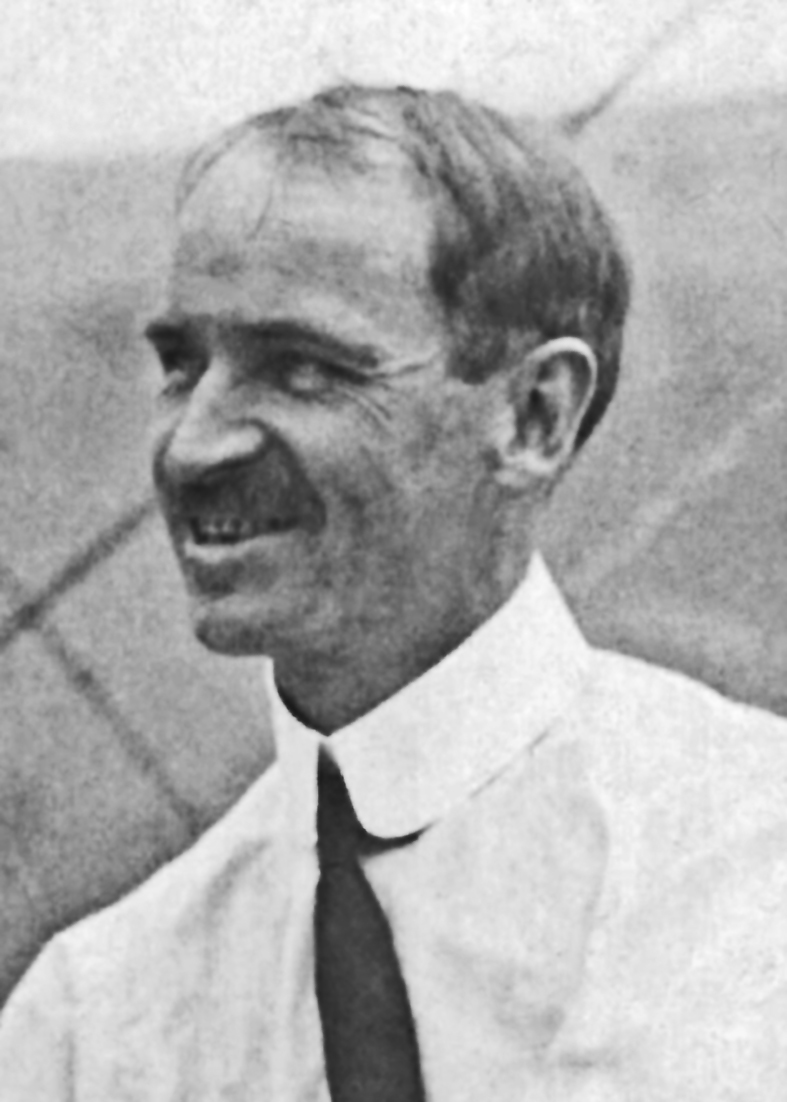

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (1878 – 1930)

On 26 January 1911, Glenn Curtiss made the first ‘practical’ hydro-aeroplane flight at North Island, San Diego Bay, California.

As a consequence, Edward Wakefield ended his negotiations with A. V. Roe & Co for a Blériot-type machine. Arrangements were then made for an Avro Curtiss-type, which when converted into a hydro-aeroplane at Windermere was known as Waterbird.

On 25 November 1911, Waterbird made the first successful flight by a hydro-aeroplane outside of France and America.

Curtiss and Wakefield shared the motivation for hydro-aeroplanes of being able to land on water in safety and also for the purpose of military scouting, rather than as an offensive weapon. Neither had an engineering degree, both working by trial and error, but had extraordinary aptitude with experts around them.

Henri Fabre had achieved the first successful flight from water on 28 March 1910 near Marseilles, but his hydravion design was not considered to be of practical use. Both Curtiss and Wakefield visited Fabre prior to their successes.

Designs and dimensions

The Curtiss pontoon float had been designed to ride through waves of the sea, shaped so that it would tend to rise on the surface. Choppy water would help overcome the suction effect of water on the float.

Initially, the main float was 5 feet long by 6 feet wide (where the rear wheels of the Model D landplane had been), with a 30 inches long float ahead (where the front wheel had been).

‘We finally made one long, flat-bottomed, scow-shaped float, twelve feet long, two feet wide, and twelve inches deep.’ – The Curtiss Aviation Book by Curtiss and Augustus Post.

‘But the great fuss stirred up by these original floats as the machine got underway preparatory to rising, and the fact that they were not suited to anything but a calm surface, caused them to be discarded shortly afterward. They were replaced by a single float, 12 feet long by 2 feet wide and 12 inches deep. … Trials showed an astonishing difference in the amount of disturbance, practically no commotion being caused even when the machine was just getting underway, while the aeroplane rose from the surface even more readily than before.’ – Practical Aeronautics by Charles B Hayward.

‘Curtiss roughed out a design for a single, narrow pontoon with a flat bottom. Robert H Baker, who ran a local machine shop, fabricated the 12-foot-by-2-float in a matter of a few days. More the result of experience and intuition than abstract hydrodynamic theory, the float was carefully contoured so that as the airplane gained speed it planed at the right attitude for takeoff. The pontoon was built up of spruce strips over a spruce frame and weighed less than half that of the tandem floats of the earlier configuration.’ – Glenn Curtiss and the Empirical Origins of Naval Aircraft Design by William F Trimble.

These were the dimensions adopted for Waterbird, but the Waterbird float was ‘stepped‘. On 11 December 1911, Wakefield applied for a UK Patent No. 27,771 for a stepped float, which was granted on 18 March 1913.

A history of the development of the step is here.

On 26 February 1911, the Triad – air, land and water – was flown by Curtiss at San Diego Bay, which was the first successful true amphibian. He added retractable main wheels under the lower wings, on either side of the main float, and a small wheel under the bow of the main float.

On 28 June 1911, Lieutenant John Towers visited the Curtiss premises concerning the 2 Navy hydro-aeroplanes being built. ‘Curtiss had sketched the plans himself with a carpenter’s pencil on the white-washed wall of the shop. Those were the only plans and that’s what they were using to build those aeroplanes! … Unfortunately a newly hired janitor decided he’d really clean up, and the first thing he did was to wash all that stuff off the wall! When they came in Monday morning, there weren’t any plans left for the plane that they were building, and Curtiss couldn’t remember what they were like!’ – Admiral John H Towers by Clark G Reynolds.

2 Curtiss hydro-aeroplanes have been purchased by the US Navy and ‘found favor on account of their shift control, which consists of a movable wheel in front of the 2 aviators and mounted upon a vertical arm pivoted at its lower end so that it can be swung in front of either man’. – Scientific American magazine, 2 December 1911.

Curtiss flying boat No. 2, nicknamed the Flying Fish, had a full-length flat-bottomed fuselage, rather than a central float. However, it would not leave the water at Lake Keuka, Hammondsport, New York until a step was added in July 1912. ‘An indication that it was built quickly and cheaply to achieve optimum performance is shown by the initial use of an old set of 1910-style single surface wings.’ – Curtiss Aircraft 1907-1947 by Peter M Bowers.

‘What is claimed to be the largest and heaviest hydro-aeroplane ever made has been recently tested on Lake Keuka. The machine has been built for Mr. Harold F. McCormick by Mr. Glenn H. Curtiss.’ – Flight magazine, 12 July 1913. The ailerons were operated by a shoulder yoke, which was fitted as standard on all Curtiss aeroplanes.

Patents

The Wright brothers submitted their first application for a US patent in 1903, when their initial Wright Flyer was still being built. In 1906, they obtained a US patent for a ‘flying machine’.

On 5 December 1911, the members of the Aerial Experiment Association, which included Curtiss, obtained US Patent No. 1,011,106 for a wingtip aileron control. That is ‘ … a pair of lateral balancing rudders … and means for simultaneously adjusting said rudders, the one to a positive and the other to a negative angle of incidence’.

On 14 September 1912, Curtiss applied for US Patent No. 1,104,036 for the Triad amphibian, which was granted on 21 July 1914.

On 4 June 1913, Curtiss applied for US Patent No. 1,142,754 for a flying boat, granted on 8 June 1915 – a red circle has been added to show the step.

On 2 December 1913, Curtiss applied for US Patent No. 1,156,215 for a hydroaeroplane with a flat-bottomed float, which was granted on 12 October 1915.

On 18 November 1916, Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Corp applied for US Patent No. 1,269,397 for a flat-bottomed pontoon float, granted on 11 June 1918.

The Wrights submitted patent infringement claims in France against Curtiss, but the proceedings took so long that the patents expired.

German courts decided against the Wright’s patent claims on the grounds that the principle of wing warping had previously been detailed. Curtiss’s German patent claim was invalidated by several French aeroplanes having previously used a similar aileron system.

Curtiss seaplanes in Europe

Curtiss established an Exhibition Company on 30 July 1910 and a Team.

The first American hydro-aeroplane flight abroad was made on 6 February 1912, when Hugh Robinson flew the Curtiss [sold to Louis Paulhan] at Juan-les-Pins, France. – Aero magazine, 17 February 1912. In March 1912, Robinson flew a Triad in the seaplane competition at Monaco.

‘Sept 5.-Glenn H. Curtiss spent today in Berlin in connection with the sale of one of his machines to the Deutsche Fluggesellschaft. The machine will eventually find its way into the hands of the German Navy Department, and duplicates will sooner or later be manufactured under German Patents. Mr. Curtiss took part this week in the naval waterplane competitions at Heiligendamm, on the Baltic. … Mr. Curtiss proceeds tonight to Belgium for the water-flying competitions there. Russia has acquired ten of his machines for use in the army and navy.’ – The New York Times, 6 September 1912.

Curtiss stated to Captain Washington Chambers of the U.S. Navy on 4 October 1912 “I have just returned from a very satisfactory trip abroad. Aviation in all its branches, and especially water-flying, is booming all over Europe, and there is a marked contrast when you reach America and find everyone sitting around and wondering what is going to be done”. ‘When World War 1 was over, the U.S. Navy had 1,865 seaplanes, 329 of which saw active service in Europe; 280 were patrol aircraft designed by Curtiss.’ – Flying Boats & Seaplanes by Stéphane Nicolaou.

The Italian Navy ordered a Paulhan-Curtiss in August 1912 and sent several officers to the school Paulhan had opened at Juan-les-Pins. (Curtiss had first met Paulhan at Reims in 1909 who built Curtiss flying boats under licence.) Subsequently 8 Curtiss flying boats were built under licence.

‘Curtiss departed New York on 30 August 1913, bound for England, France and other European countries on a whirlwind tour to sell flying boats and hydroairplanes. … Curtiss himself demonstrated his new Model F flying boat on the south east coast of England, hoping that it would garner orders from wealthy sportsman fliers. … Curtiss returned from Bremen, reaching New York on 26 October.’ – HERO OF THE AIR GLENN CURTISS and the Birth of Naval Aviation by William F Trimble.

‘LONDON, Tuesday, Sept. 30.-A telegram to The Morning Post from Odessa says: “Glenn Curtiss is expected shortly at St. Petersburg. It is credibly stated that the chief object of his visit is to obtain a concession for the establishment of an aeroplane factory in Russia. … Twenty Curtiss hydro-aeroplanes received at Sevastopol last year by the Naval and Military Aero Club have given the fullest satisfaction. The naval and military hydro-aeroplane pilots at Sevastopol were trained by Charles Witmer, an expert member of the Curtiss aerial staff sent out specially from New York.” – The New York Times, 30 September 1913. In 1915, Curtiss supplied more than 50 Model K aircraft to Russia.

‘With not enough work to make his Hammondsport factory pay, Curtiss left New York on 3 December 1913, planning to attend an aeronautics show in Paris before heading to the south of France. On 13 January word came that the federal appeals court had upheld the Wright patent case. Leaving from Naples where he was to demonstrate the flying boat for the Italian government, Curtiss sailed on 1 February to New York.’ – HERO OF THE AIR by William F Trimble.

Curtiss seaplanes in England

Captain Ernest Bass was the first to introduce Curtiss flying boats and engines to England and held the sole concession before transferring the business to a syndicate headed by White & Thompson Ltd of Bognor.

The first Curtiss seaplane, a version of the Model F, came to Brighton in October 1913. Modifications were made, including a Deperdussin dual control instead of the shoulder-strap. It was sold to Bass and taken to the south of France in the spring of 1914, but returned for rebuilding due to a crash and then known as the Bass-Curtiss Airboat.

Curtiss was based at Paris, but had to return to America to fight the 4th round of the Wright brothers’ patents court action.

In 1914, John Porte went to America to join Curtiss who had been commissioned to produce a flying boat capable of crossing the Atlantic and to claim the Daily Mail £10,000 prize, which was named America. However, World War 1 intervened, but the name became generic for future models.

On Porte’s arrival back in England, he entered the Royal Naval Air Service as a Squadron Commander at Royal Naval Air Station Hendon. Having been transferred to RNAS Felixstowe, he was given command in 1915. He obtained Admiralty permission to purchase 2 Curtiss flying boats, and there followed 62 Curtiss H-4 Small America and 71 H-12 Large America flying boats. Porte carried out many improvements and, during experiments on the Curtiss hulls, work began on the construction of large flying boats leading to the Felixstowe F-boats. The F-boats were essentially Curtiss; Porte’s principal contribution to the design was an improved hull.

‘At Messrs. Curtiss’s works we placed a very able inspector and one of the first to gain his pilot’s certificate [No. 11] in this country, Lieutenant Commander Maurice Egerton. All the data we gained in actual flying experience in the North Sea we passed through Egerton to the Curtiss Co. Consequently, that firm was well up to date when America came into the War.’ – Airmen or Noahs by Rear Admiral Murray Sueter.

Britain became the largest overseas customer of Curtiss during the War. The H-16 flying boat contract was overseen by Egerton. For more information about Egerton, click here and see under ENGINES.

On 20 May 1917, 2 ex-Windermere pupils, Flight Sub-Lieutenants Charles Morrish and Henry Boswell, whilst flying an H-12 based at Felixstowe, were officially credited with the first sinking of a U-boat by the RNAS. Both received the Distinguished Service Cross.

A Felixstowe F.2A flying boat, based at Killingholme, shot down a Zeppelin on 10 May 1918, whilst under the command of Captain Cooper Pattinson of Windermere. Pattinson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Felixstowe F.3 flying boat hulls were made by Borwick & Sons, boat builders of Bowness-on-Windermere, having been sub-contracted in 1918 by Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd of Preston.

On 31 May 1919, a Curtiss NC-4 under Lieutenant Commander (later Rear Admiral) Albert ‘Putty’ Read became the first aeroplane to fly across the Atlantic, when delivered from New York to Plymouth. By Navy edict, crews were ineligible for the Daily Mail’s prize; on 15 June John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the trip and were presented with the prize by Winston Churchill.

The Aéro-Club de France began issuing Aviators’ Certificates from 1 January 1910, but the first 16 were retrospectively dated for aviators who had already demonstrated their abilities. So, Curtiss received Licence No. 2 dated 7 October 1909, having, for example, won the Gordon Bennett speed trophy race at the Reims Aviation Meeting on 28 August 1909 when he had been chosen to represent America.

On 8 June 1911, Curtiss was awarded Aviator’s Certificate No. 1 by the Aero Club of America.

Hugh Robinson held Aviator’s Certificate No. 42. ‘The identity of the actual inventor of this crude progenitor of the aircraft carrier arresting gear used in 1911 is a matter of some debate. One compelling version of the story says that Hugh A. Robinson gave Lt. Theodore Ellyson the idea. Robinson, a former trick bicycle and motorcycle performer, allegedly adopted the aircraft arresting system from a similar one he had developed years earlier for a circus act in which a young lady rode a small cart down a steep track at a high rate of speed.’ – FOR THE GREATEST ACHIEVEMENT A History of the Aero Club of America and the National Aeronautic Association by Bill Robie.

Aviators’ Certificates in France, America and the UK were then recognised by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (‘FAI’).

Louis Paulhan held Aviator’s Certificate No. 3, having been issued an FAI Certificate No. 10 from the Aéro-Club de France on 17 August 1909 which was before the Aero Club of America began issuing Certificates. His accomplishments included flying at the Blackpool Aviation Week in 1909 which was attended by Wakefield and in 1910 he flew Fabre’s hydravion.

– ‘I got more pleasure out of flying the new machine over water than I ever got out of flying over land, and the danger, too, was greatly lessened.’ – The Curtiss Aviation Book.