WORLD WAR 1 AVIATION AND WINDERMERE

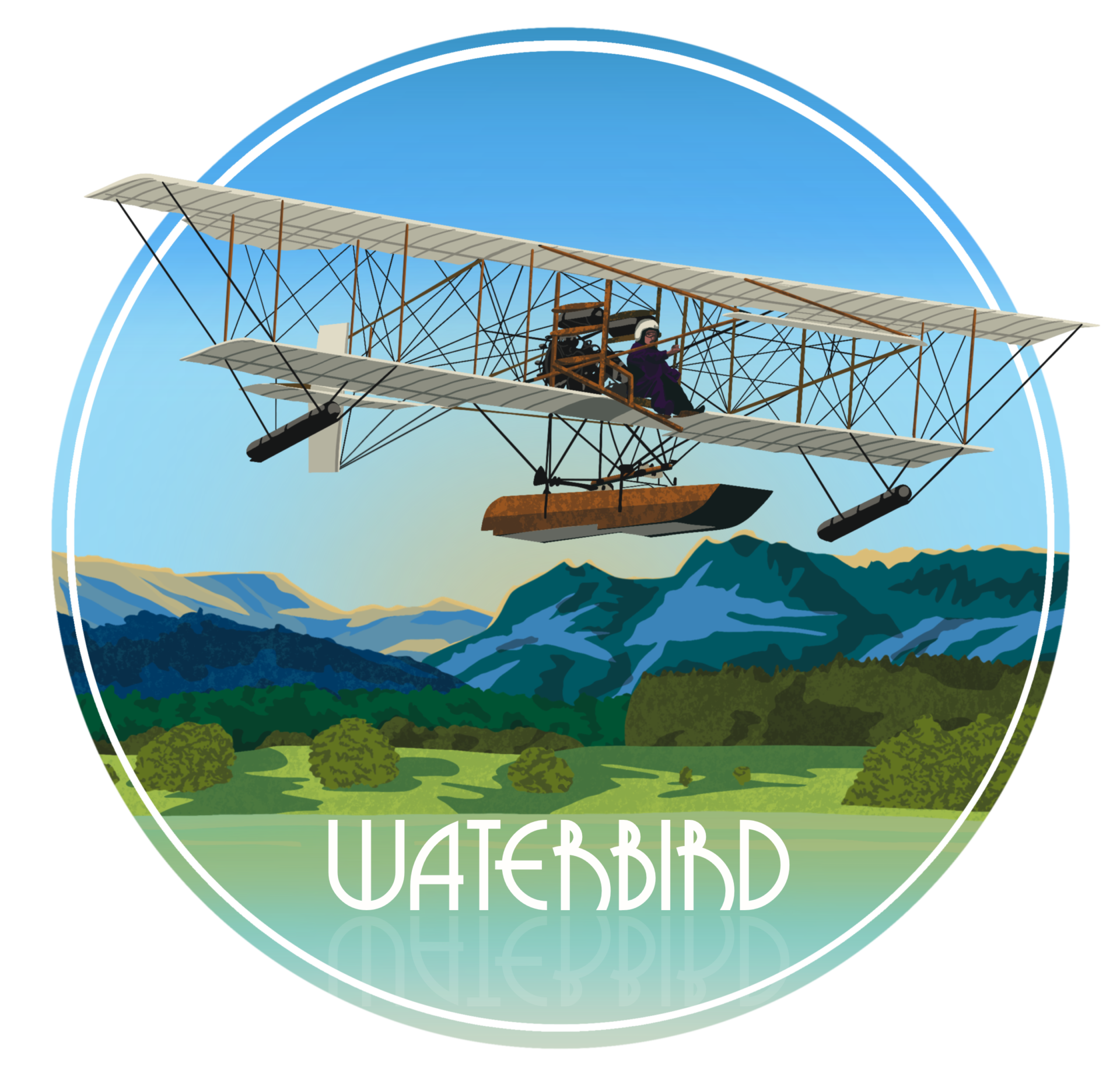

CAPTAIN EDWARD WAKEFIELD AND WATERBIRD

On 25 November 1911, from Windermere, Waterbird had achieved the world’s first successful flight to use a ‘stepped’ float. Waterbird was an Avro Curtiss-type hydro-aeroplane. The pilot was Herbert Stanley Adams (later Lieutenant Colonel, DSC, MBE).

Waterbird was commissioned by Captain Edward Wakefield from A. V. Roe & Company.

When Lieutenant (later Air Chief Marshal Sir, GCB, DSO, DL) Arthur Longmore flew Waterbird on 20 January 1912, he became the first member of the Royal Navy to successfully take off and land a hydro-aeroplane. Within Wakefield’s invitation to the Admiralty, leading to Longmore going up to Windermere, he mentioned the possibility of training pilots.

Wakefield patented the stepped float and means of attachment, for which he entered into a secret contract on 14 March 1912 with the Admiralty, and also to convert a Deperdussin, Admiralty serial M.1, to a hydro-aeroplane.

‘We believe that with the exception of the hydroaeroplanes of the United States Navy no other machine of like nature has been so successful. … For the fame of Mr. Wakefield himself and Windermere it is to be hoped that the Admiralty may take the matter up so that we may not be left behind by any other European power.’ – Kendal Mercury and Times, 22 December 1911.

DEPERDUSSIN AT WINDERMERE

The dismantled Admiralty Deperdussin arrived by rail at Lakeside on 13 June 1912, and was then conveyed by barge to Hill of Oaks. Having been converted successfully from a landplane, flights at the lake during July were accomplished by Adams, Lieutenant (later Acting Commander) Reginald Gregory and Lieutenant (later Air Commodore, CMG, DSO and Bar, AFC) Charles Samson.

DEVELOPMENTS ELSEWHERE

On 10 January 1912, off Sheerness, Samson had achieved the first launch from a British warship by flying an aeroplane fitted with airbags – HMS Africa, and on 9 May 1912, off Weymouth, the first take-off from a moving ship, with a second flight by Gregory – HMS Hibernia, as described in the Illustrated London News of 18 May.

The Royal Navy established the first Air Station at the Isle of Grain, situated at the mouth of the River Thames. – Flight magazine, 4 January 1913.

QUOTES

‘Many, who along with me learnt during the war in South Africa, the value of scouting, believe that scouting by hydro-aeroplane will shortly become a necessity for the safety of this island. England is too far behind other powers in aircraft and in flying men for both Army and Navy.’ – Letter from Wakefield to The Times, 11 January 1912.

‘Edward Wakefield was convinced that the future for Naval hydro-aeroplanes lay in scouting for the fleet and relaying back information – extending the Naval battle space over the horizon. He knew that Naval aircraft could be the eyes and ears of the fleet.’ – Commander Sue Eagles, Navy Wings.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PRIVATE ENTERPRISE

On 28 February 1912, the secret Report of the Technical Sub-Committee of the Standing Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence on Aerial Navigation was approved. The Report recommended that the Naval Wing of the Flying Corps should be established and that it attached importance to the maintenance of private enterprise in the field of aeronautics. The Report included ‘It is impossible to over-estimate the importance of experiments for the development of hydro-aeroplanes’.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty and a member of the Standing Sub-Committee, when asked in the House of Commons about the Royal Navy and hydro-aeroplanes, referred to the experiments at Windermere and that ‘the results so far attained have been promising’.

On 16 April 1912, Churchill confirmed in the Commons that private hydro-aeroplane tests would continue on Windermere. Click here for extract from Hansard.

The term ‘Seaplane’ was coined by Churchill, when he answered a question in the Commons on 17 July 1913.

In 1918, Borwick & Sons, boat builders of Bowness-on-Windermere, were sub-contracted by Dick, Kerr and Company Ltd of Preston to construct hulls for Felixstowe F.3 flying boats.

SEAPLANES IN WAR

Churchill wrote in a Minute of 10 February 1914 that ‘The objectives of land aeroplanes can never be so definite or important as the objectives of seaplanes, which, when they carry torpedoes, may prove capable of playing a decisive part in operations against capital ships. The facilities of reconnaissance at sea, where hostile vessels can be sighted at enormous distances while the seaplane remains out of possible range, offer a far wider prospect even in the domain of information to seaplanes than to land aeroplanes’.

Whilst Wakefield advocated defensive scouting, derived from his experience in the Boer War, Churchill, however, came to the view that attack was the prime tactic for defence: ‘The great defence against aerial menace is to attack the enemy’s aircraft as near as possible to their point of departure’.

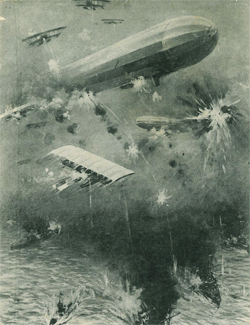

3 years and 1 month after Waterbird’s first flight, carrier-borne seaplanes were launched against Germany. ‘The Cuxhaven raid marks the first employment of the seaplanes of the Royal Naval Air Service in an attack on the enemy’s harbours from the sea, and, apart from the results achieved, is an occasion of historical moment. Not only so, but for the first time in history a naval attack has been delivered simultaneously above, on, and from below the surface of the water.’ – Flight magazine, 1 January 1915.

TRAINING TO FLY SEAPLANES AT WINDERMERE

The first private British Seaplane School was formed in 1911 at Hill of Oaks on the south east shore of Windermere.

On 23 January 1912, Rear Admiral (later Admiral Sir, KCMG, CB, MVO) Ernest Troubridge, Chief of Staff, published a paper on The Development of Naval Aeroplanes. For the obtaining of personnel, he proposed ‘Bristol school or Wakefield hydro-aeroplane school to train those pilots that cannot be received at Eastchurch at present’.

When Second Lieutenant (later Major, OBE) John Trotter was awarded his Aviator’s Certificate on 12 November 1912, he became the first member of the Military to achieve a UK Certificate with tests taken on a hydro-aeroplane.

For examples of the fates of Windermere students, click here

Following the outbreak of war, Wakefield joined the Cheshire Regiment becoming commander of a Labour Battalion on the Western Front.

On 11 November 1914, the Hill of Oaks hangars were leased, the Cockshott hangar lease was assigned, and Waterhen, Seabird and the Lakes Monoplane were sold by The Lakes Flying Company to The Northern Aircraft Company Ltd. In 1916, a double hangar was added at Hill of Oaks to the south of the existing hangars.

‘Large numbers of probationary Sub-Lieutenants R.N. were sent to Windermere for basic instruction, in addition to those who had already qualified on land machines.’ – Britain’s Seaplane Pioneers by M H Goodall, Air Pictorial, January 1988.

The School was taken over on behalf of the Government, and in May 1916 training operations at Cockshott and Hill of Oaks became RNAS Unit Hill of Oaks. The first planned flying course under the total control of RNAS Hill of Oaks began on 3 May 1916. The course had an international element in that it included 10 Canadians.

In June 1916, the headquarters of the RNAS at Windermere moved from Cockshott to Hill of Oaks, and, with the departure of civilian instructors, the name was changed to RNAS Windermere.

A Royal Naval Air Station was established at Hill of Oaks 1916-1917.

The fleet included, at various times: 4 Nieuport VI.H seaplanes, 9 F.B.A. Type A flying boats and 3 Short 827 seaplanes. This photo is of F.B.A. 3206, with Short 3328 flying by.

The first pupil to obtain a Hydro-aeroplane Certificate at RNAS Hill of Oaks was Flight Sub-Lieutenant Paul Gadbois, on 14 June 1916. He departed Windermere on 26 June 1916, but 2 weeks later was seriously injured in a seaplane accident. The last pupil to obtain a Certificate at Windermere was Edward Haller, on 16 August 1916. He joined the RFC, but was killed on 3 June 1917, when shot down flying a Sopwith 1½ Strutter.

Whilst giving instruction on 2 September 1916, Flight Lieutenant Harold Bower was killed when F.B.A. 3648 broke up during the approach to alight. The fuselage had been significantly weakened during an earlier heavy landing. Flight Sub-Lieutenant Ernest Forsyth-Thompson escaped with minor injuries and shock.

RNAS personnel involved themselves in the local community, even putting on a concert. However, parents of daughters complained that the prefix to RNAS Hill of Oaks stood for Rather Naughty After Sunset!

For a Book of Remembrance, click here

WINDERMERE ACHIEVEMENTS

- Windermere graduates, Flight Sub-Lieutenants Charles Morrish and Henry Boswell, were credited officially with the first aerial sinking of a U-boat. On 22 June 1917, both of them were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (‘DSC’).

- On 22 June 1917, Windermere graduate Flight Sub-Lieutenant Charles McNicoll was also awarded the DSC, for convoy protection and combatting submarines.

- After RNAS Calshot and RNAS Killingholme, Adams was posted to the Dardanelles. On 25 November 1916, he led a flight of 9 Nieuport aeroplanes from RNAS Imbros, Turkey to Bucharest. On 13 July 1916, he was Mentioned in Despatches, and on 1 October 1917, was awarded the DSC for services in the Eastern Mediterranean.

- Flight Commander Guy Price, a Windermere instructor in 1916, was posted to France and awarded the DSC on 22 February 1918 with a Bar on 16 March 1918, an ace having downed 12 enemy aeroplanes.

- Flight Lieutenant John Hume, who began his training at Windermere in 1915, was awarded the DSC posthumously on 17 March 1918 for services during the Mesopotamia campaign.

- On 10 May 1918, Captain Cooper Pattinson from Windermere was first pilot of an S.E. Saunders Ltd-built Felixstowe flying boat which shot down a Zeppelin at Heligoland Bight, for which he was within the first recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (‘DFC’). Also, on 16 May 1918, whilst carrying out an anti-submarine patrol, he achieved the record for the longest duration flight for a flying boat during World War 1 at that time of 9 hours 45 minutes.

- On 3 June 1918, ex-Windermere pupils Captains Harold Gonyon and Victor Bessette (both Canadian) were also amongst the first recipients of the DFC, for respectively bombing a U-boat and for services over the North Sea.

- On 18 June 1918, ex-Windermere instructor Acting Flight Commander Paul Robertson was awarded the Albert Medal, exchanged for the George Cross, for endeavouring to extricate a pilot following a seaplane crash.

- Having taken part in the ‘most outstandingly successful carrier operation of the war’ on 19 July 1918, ex-Windermere pupil Captain William Dickson was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. He became Marshal of the RAF.

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT WAVELL WAKEFIELD

On 1 November 1918, Wavell Wakefield (Edward Wakefield’s nephew, later Lord Wakefield of Kendal) landed and took off a Sopwith Pup on the after deck of HMS Vindictive at Scapa Flow. He was one of the very few pilots to fly over the surrendering German fleet. He was mentioned in the London Gazette of 3 June 1919 for gallant and distinguished services, signed by Churchill as Secretary of State for Air.

CAPTAIN ARTHUR WAKEFIELD

Doctor Arthur Wakefield (Edward Wakefield’s brother), whose service included at a casualty clearing station during the Battle of the Somme, unveiled a memorial on 8 June 1924 at the summit of Great Gable to the 20 members of The Fell and Rock Climbing Club who were killed in World War 1. He was a member of the 1922 Mount Everest expedition, which included George Mallory.