SEAPLANE HISTORY AT WINDERMERE

THE AWARD-WINNING REPLICA WATERBIRD FLYING FROM WINDERMERE IS A WORLD CLASS EXPERIENCE

Putting the 1911 replica Waterbird into perspective in relation to other current historic airworthy examples of seaplanes in the world within the era

Originals:

1929 Hamilton Metalplane H-47 in the USA

1935 Caproni Ca.100 in Italy.

Restoration:

1930 Sikorsky S-39 in the USA.

Replica:

None.

The following, from the North-West Evening Mail, sets the stunning scene

‘The replica Waterbird – regardless of whether it flew just once or a dozen times – would become an important part of local history.

‘I certainly think it is important to celebrate Windermere’s cultural heritage and cultural heritage isn’t just about its landscape and literary associations.

‘Its industrial heritage and boat building and seaplane building is just as a legitimate part of Windermere’s history.’

– Bob Cartwright.

Prior permission

In order to operate a seaplane on Windermere, it is necessary to first obtain permission from The Lake District National Park Authority under the power granted to it by byelaw 12.5 of the Windermere Navigation Byelaws 2008. That is, exemption from byelaw 12.3 which prohibits speed greater than 10 knots per hour, and from byelaw 17.1 which prohibits an aeroplane from being navigated on the surface. The change to 10 knots per hour, rather than 10 miles per hour, was introduced on 13 October 2012, with other bodies of water left at mph.

A history of speed limits on Windermere is within the section below headed ‘PROTESTS’.

STEAMBOATS

The golden age of the lake was from the late 19th century until the early 20th century

Steamboats and hydro-aeroplanes: this montage of Waterhen flying over steam cargoboat Raven, which operated at the lake 1871-1922, ‘evokes something of the drama of the time and the growing ascendance of the petrol engine over steam’. – The Great Age of Steam on Windermere by G H Pattinson. Waterbird was built in 1911; the same year as steam launch Swallow, which is the sister ship of Osprey and Shamrock – the builder of all 3 boats was Shepherds of Bowness-on-Windermere. When a Sunderland flying boat (1990) and a Catalina flying boat (1994) visited the lake, Shamrock acted as tender. This photo, taken on 25 August 1913, includes Waterhen and saloon launch Lily (later re-named Branksome).

Swift, the biggest vessel to have been launched on the lake, was in service 1900-1981 being the last coal-powered vessel commissioned by the Furness Railway Company. Swan operated 1869-1938, described by Pattinson as a ‘particularly fine and fast steamer’. Teal had a career of 50 years: 1879-1929.

All historical photos at Windermere on this website were taken by Frank Herbert, unless otherwise stated.

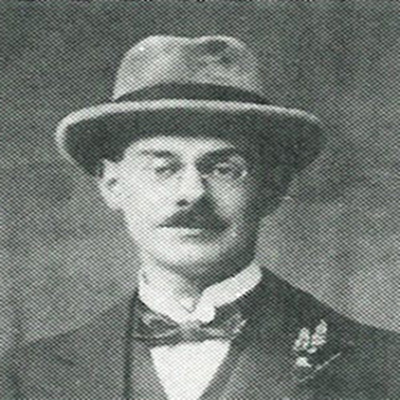

CAPTAIN EDWARD WAKEFIELD

During 18-20 October 1909, Wakefield attended at the Blackpool Aviation Week. It was Great Britain’s first official meeting, being recognised by the Aero Club (the Doncaster Meeting was not sanctioned as the Club considered that in the infancy of aviation it was not in the interest of this new sport to hold concurrent meetings). ‘A suggestion had been mooted by several members of the Carlisle Chamber of Commerce that Burgh Marsh and the adjoining lowlands along the Solway Firth, to the north-west of Carlisle, would form a suitable place at which to hold a flying meeting.’ – Flight magazine, 18 September 1909.

At Blackpool, Wakefield saw flying machines for the first time, including that of Alliott Verdon Roe about which he wrote on 19 October. Reaching a height of 225 feet created enormous enthusiasm and 40 miles per hour was considered to be ‘exceedingly fast’. He described witnessing accidents to Hubert Latham’s Antoinette aeroplane when it came down too suddenly and to Henri Rougier’s Voisin which was caught by a gust. At a time when an aeroplane capable of rising from and alighting upon water was described in Flight magazine as ‘scarcely even dreamt of’, he concluded that in the event of structural or engine failure it would be safer to land on water. However, his pioneering theory was ridiculed by the leading experts who were present.

On 1 March 1910, Wakefield was elected as a member of The Royal Aero Club. He was a Vice President of The Lancashire Aero Club, Blackpool.

Wakefield commissioned A. V. Roe & Company (‘Avro‘) to build Waterbird, an Avro Curtiss-type. He switched from a Blériot-type upon the world’s first practical hydro-aeroplane flight by Glenn Curtiss on 26 January 1911 at San Diego Bay, California. A brief note of cabled information about the feat appeared in Flight magazine of 4 February 1911, followed by an article on 25 February. The Aeronautical Journal of April 1911, declared that the Curtiss float was 12 feet long, 2 feet wide and 1 foot deep, which were the measurements of Waterbird’s float.

Curtiss, with the same motivation as Wakefield, wrote ‘I knew it would be safer to land on the water than on land with the proper appliances, and that it would be easier to find a suitable landing place on water, for the reason that it always affords an open space, while it is often difficult to pick a landing place on the land’. – The Curtiss Aviation Book.

Construction took place at Brownsfield Mills, Manchester, testing at Brooklands and transportation by train to Windermere on 7 July 1911 where conversion took place to a hydro-aeroplane.

However, delay was caused by the defective condition of the engine, such that it could not have been used safely and was taken to the Gnome Engine Company’s works in Paris for repair. This escalated into High Court proceedings by Avro against Wakefield, which he defended and met with a counterclaim.

The drawings are the oldest surviving of any Avro aeroplane.

A rudder is the oldest surviving part carrying the legend ‘A. V. Roe & Co’.

The first task at Windermere for Wakefield was to have a hangar designed and built, with an office and store. The site which he chose was land he owned at Hill of Oaks, on the south-east shore of the lake. He also acquired a motor launch and had a wet dock built for it. However, whilst this location was ideal for float experiments, it proved too out of the way for business and he wanted to come to Bowness-on-Windermere, where he took out a lease of land at Cockshott in 1912.

Success with Waterbird only came after what Wakefield described as “two years hard”. He carried out a “long and rather tedious, but interesting series of experiments with floats of many shapes and sizes, towed by the motor launch” and carefully studied all that had been achieved abroad.

Having first checked that Oscar Gnosspelius was not making his expected attempt from Bowness Bay, on 25 November 1911 Waterbird took off successfully from Windermere and alighted. The pilot was Herbert Stanley Adams, whom Wakefield had met at Brooklands. Adams sent Wakefield a telegram: ‘Several short flights no damage’. A report appeared in the Manchester Guardian on 27 November.

Waterbird ‘had the distinction of being the first successful British hydro-aeroplane.’ – Flight magazine, 7 December 1912. More precisely, the first outside of France and the USA. The world’s first successful flight to use a stepped float, it was only achieved after considerable experimentation by Wakefield over 2 years and when a second step was added at the stern. The design of floats had become a science of its own. The floats were built by Borwick & Sons, boat builders of Bowness.

Photographs of Waterbird in action and text occupied the entire front page of magazines: The Car (24 January 1912), The Aeroplane (25 January 1912), Flight (27 January 1912) and The Aero (February 1912). Also, there was a feature in the French magazine Le Plein Air (16 February 1912).

The above Aeroplane magazine article included that, in spite of bad weather, Waterbird had by then made about 60 flights over 38 days, the furthest for 20 miles and up to 800 feet and was regarded as being extremely successful. This photo was taken on 18 January.

The Westmorland Gazette of 24 February 1912 reported not only on a successful flight by Gnosspelius but also on experiments by Wakefield to enable the carrying of a passenger. Such a flight by Waterbird culminated in a landing when the float dipped and went under the water so that the whole structure submerged. Adams and Wakefield escaped with a wetting and Waterbird was none the worse. Recovery was carried out by Borwicks using a barge fitted with a pile-driver.

However, disaster struck on 29 March 1912, when Waterbird was written off in a hangar collapse at Cockshott because of a gale. Photographs of surviving parts are here. For what happened to the parts, please see here.

On 11 December 1911, Wakefield submitted UK Patents No. 27,770 and No. 27,771 relating to the means for float attachment including rubber bungees for shock absorption when taking off and alighting, and a stepped float, which were granted respectively on 12 September 1912 and 18 March 1913. The first patent for a stepped hydroplane, for a boat, had been granted in 1907 to Albert Knight. Today, all seaplane floats have steps. Also, on 13 November 1913, Wakefield was granted UK Patent No. 18,051 for the float of a seaplane to support its own weight or the greater part of such weight during flight.

For an interactive 3D model of the replica Waterbird, please click here

BARROW-IN-FURNESS

On 18 November 1911, at Cavendish Dock, Barrow-in-Furness, an Avro D had taken off. Fitted with a pair of stepped floats, it left the water for 50 or 60 yards in skips. The pilot was Commander (later Air Vice-Marshal Sir, KCB CBE) Oliver Schwann (later Swann). However, he had only taught himself basic pilot skills and was unprepared for the sudden climb to a height of 15 or 20 feet. The aeroplane fell back into the water, damaging the floats and smashing up the port lower wing.

‘Although it flew some [seven] days after Commander Schwann, Waterbird was generally regarded as the first successful British seaplane.’ – Avro: The History of an Aircraft Company by H Holmes.

Schwann was among the founder members of the Hermione Flying Club at Barrow, which included Lieutenant Eugene Gerrard (one of the first 4 officers selected for flying training by the Admiralty, later Air Commodore) and Captain (later Rear Admiral Sir, CB) Murray Sueter. Flying was carried out privately, not as a Royal Navy officer.

On 2 April 1912, the Avro D achieved the first successful flight from seawater in Britain, when the pilot was Sydney Sippe (later Major, DSO OBE FRAeS). Sippe had been asked by Schwann to come up to Barrow to prove the Avro D’s capability. Sippe is 2nd from left in this photo, taken at the French airship base at Belfort on 21 November 1914 just before he flew an Avro 504 (No. 873) to attack the Zeppelin factory at Friedrichshafen. For his gallantry, Sippe received the Distinguished Service Order and the French Légion d’honneur. This raid was part of the world’s first strategic bombing campaign.

OSCAR GNOSSPELIUS

Gnosspelius (later Major), like Wakefield, was inspired by attending the Blackpool Aviation Meeting. Following a letter of introduction from the Lancashire Aero Club, they both visited Henri Fabre at Paris in October 1910 where he was exhibiting his hydravion which had made the world’s first flight from water on 28 March 1910 near Marseilles. Gnosspelius No. 1 was underpowered and did not take off.

Gnosspelius No. 2

Earlier in the day than Waterbird’s first flight on 25 November 1911, Gnosspelius No. 2 had been going for a minute when there was an untoward gust of wind causing Gnosspelius to lose control. He had been instructed by Howard Pixton (later Captain) at Brooklands, but limited to flying straight and level. He overcorrected, causing a rapid bank to the right and then to the left, following which a wingtip was damaged and the propeller splintered upon striking the water, resulting in the aeroplane turning over onto its back.

On 14 February 1912, the experiments by Gnosspelius were crowned when he flew Gnosspelius No. 2. It was the first successful flight by a hydro-monoplane in Britain.

Gnosspelius No. 1 and Gnosspelius No. 2 were both monoplanes, whereas Waterbird, the Avro D and Waterhen were all hydro-biplanes.

Ronald Kemp flew Gnosspelius No. 2 in April. Kemp had test-flown Waterbird as a landplane at Brooklands on 27 June 1911. ‘Mr. Sippe’s experiences with the Avro and Mr. Kemp’s tests with the Gnosspelius No. 2 have shown that the engine-in-front type can be quite as successful as the box-type.’ – The Aeroplane magazine, 2 May 1912.

Waterbird and Waterhen had a 50 horse power Gnome engine, the Avro D a 35 horse power Green engine and Gnosspelius No. 2 a 50 horse power Clerget engine.

The first flight of Waterhen – Waterbird’s successor – took place on 30 April 1912. Built locally, Waterhen was distinguishable from Waterbird by straight trailing edges of the ailerons and a much broader central float of 6 feet so as to enable Waterhen to carry a passenger. Waterhen was included in Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft 1913, and detail requested for the 1914 edition.

This photograph was taken from Waterhen at 200 feet adjacent to Hill of Oaks looking north.

Whilst staying at the Old England Hotel, Bowness-on-Windermere, Herbert à. Brassard went up for a pleasure flight in Waterhen from Cockshott at the end of May 1912 at a cost of 4 gold sovereigns. ‘ … The engine spluttered into noisy but rhythmical revolutions. I recollect we taxied for some 50 yards and took off smoothly and so flew around Lake Windermere for some 20 minutes in all. It was interesting and not frightening at all but I did shiver with the cold air rushing around me. I remember that, when banking, I felt not unpleasantly glued to the chair, a gyroscopic effect, and there was no inclination for me to slip sideways or lean to the opposite direction. One was, or seemed to be, at the same angle as the plane. Flying “downhill” to land on the Lake was thrillingly speedy and there was no need to lean backwards or tend to fall forwards. Touching down was remarkably smooth and without much splash. And so back to the sheds.’ – Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society, November 1960.

A water rudder, attached to the air rudder, was briefly used in 1912. An enclosed nacelle with a pointed front, to protect the occupants from the elements, was added in the winter 1912/1913. On 9 October 1913, an altimeter and airspeed indicator were fitted. 2 floats (Note the cafe beyond the far hangar) with a new undercarriage were installed during the winter 1913/1914, when the wingtip floats were detached.

Highlights included:-

- The first successful British passenger [Wakefield] flight in a hydro-aeroplane on 3 May 1912

- The first UK flight for instructing a pilot on a hydro-aeroplane on 9 September 1912

- The tests for the first UK’s Aviator’s Certificate accomplished on a hydro-aeroplane on 12 November 1912

- Gertrude Bacon became the first woman in the world as a passenger in a hydro-aeroplane and the first person to make a complete circuit of the lake on 15 July 1912

- A new method of transmitting wireless messages from air to ground on 19 July 1912

- An exhibition at Windermere Agricultural Show on 8 August 1912

- Taking up passengers, including the local MP Stanley Wilson, from Hornsea Mere during the Hornsea Horse Show on 12 June 1913

- The first Windermere flight with 2 passengers on 25 August 1913

- The tests for the first UK hydro-aeroplane aviator’s certificate on 30 August 1913

- The first landing/take-off at Esthwaite Water on 21 October 1915

- The tests for the last Aviator’s Certificate at Windermere on 16 August 1916.

BLÉRIOT XI

The Blériot XI, here shown with 6 aboard to test float buoyancy, has an intriguing background. It was described in Britain’s Seaplane Pioneers by M H Goodall, Air Pictorial December 1987 as being ‘added to the fleet in 1912’, and was listed in the About the Seaplane School booklet by Fleming-Williams of early 1915. The only known flights at Windermere were on 11 and 15 June 1915, being logged by Donald Macaskie for his first solo. The booklet refers to a 40hp Humber engine, but the log book has it as 35hp. The pointed central float, in the foreground of this photograph, was formerly used by the Gnosspelius-Trotter.

THE LAKES FLYING COMPANY

The Lakes Flying Company was established by Wakefield on 20 December 1911. The patron was Lord Lonsdale, who owned the lake bed, with Adams as Manager. The declared intentions were to build aeroplanes, experiment, teach pupils and give exhibitions. The first British hydro-aeroplane school was created. A logo was designed and adverts placed.

WAKEFIELD’S ACHIEVEMENT AND VISION

Wakefield’s success brought congratulatory letters, telegrams and acknowledgements. They included from Schwann, and from the mother of Gnosspelius

‘We believe that with the exception of the hydro-aeroplanes of the United States Navy no other machine of like nature has been so successful. The importance of these facts in connection with harbour, estuary and coast defence and scouting need hardly be remarked upon. For the fame of Mr. Wakefield himself and Windermere it is to be hoped that the Admiralty may take the matter up so that we may not be left behind by any other European power.’ – Kendal Mercury and Times, 22 December 1911.

‘Why are we so behind our Continental friends in aircraft. Think of our coasts all patrolled and protected by these machines. Think of our Dreadnoughts guided and warned by flying scouts. What a sense of safety and what greatly increased efficiency it would give them!’ – Wakefield in the Daily Express, 12 January 1912.

‘At the moment we are chiefly concerned with coast defence work, until the various stations are properly equipped.’ – The Aeroplane magazine, 31 July 1913.

Revd Swann, Vicar of St Lawrence, Crosby Ravensworth near Shap (1905-1912), also sent a letter to Wakefield. He was another to have been to the Blackpool Aviation Meeting. In 1909, he had a monoplane built by the Austin Motor Company Ltd at Aintree Racecourse and in 1910 a biplane with help from 2 local joiners at Meaburn Hall 1 ½ miles to the north of Crosby Ravensworth, but neither was successful. His life story is set out in a display at the Church.

THE ADMIRALTY

Lieutenant Arthur Longmore (one of the first 4 officers selected for flying training by the Admiralty at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, off Kent, and later Air Chief Marshal Sir) test-flew Waterbird for the Admiralty on 20 January 1912. He compiled a Report © Trustees of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, now held at the Fleet Air Arm Museum, concluding that ‘the float and undercarriage are excellent’.

The Admiralty took an early keen interest in the hydro-aeroplane school at Windermere. Rear Admiral (later Admiral Sir) Ernest Troubridge, Chief of Staff, compiled a paper on The Development of Naval Aeroplanes on 23 January 1912. For the obtaining of personnel, he proposed ‘Bristol school or Wakefield hydro-aeroplane school to train those pilots that cannot be received at Eastchurch at present’.

Wakefield entered into a contract on 14 March 1912 with the Admiralty for floats and undercarriages, or royalties, and to convert Admiralty Deperdussin M.1 (a monoplane) into a hydro-aeroplane; following initial communication with Captain (later Rear Admiral Sir) Godfrey Paine of HMS Actaeon at Sheerness. The contract was expressed to be ‘subject to the Official Secrets Act’.

The Deperdussin was delivered on 5 June 1912 and accepted for the Admiralty at Windermere on 24 July 1912 by Lieutenant (later Commander) Reginald Gregory (one of the first 4 officers selected for flying training by the Admiralty and a member of the Technical Sub-Committee of the Standing Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence on Aerial Navigation (‘C.I.D.’)), and he flew it the following day. Commander Charles Samson (one of the first 4 officers selected for flying training by the Admiralty, the first pilot to take off from a British warship on 10 January 1912 and the first from a moving ship on 2 May 1912, a member of both the C.I.D. and its Technical Sub-Committee, and later Air Commodore) had flown in the Avro D at Brooklands on 12 May 1911 and flew in the Deperdussin at Windermere.

PASSENGER WORLD FIRSTS AT WINDERMERE

Edward Wakefield

‘I should say that you are certainly the first [in the world] passenger in a hydro-monoplane.’ – A letter of 17 July 1912 from C. G. Grey, Editor of The Aeroplane magazine, to Wakefield, after flying at Windermere in the Admiralty Deperdussin which he had converted into a hydro-aeroplane within 4 weeks of delivery.

‘The Lakes Flying Company had a share in producing, we believe, the first hydro-monoplane to lift passengers.’ – Flight magazine, 7 December 1912.

Gertrude Bacon

In July 1912, Gertrude Bacon flew in Waterhen becoming the first woman in the world to make a passenger flight in a hydro-aeroplane, and in the Deperdussin becoming the first woman in the world to make a passenger flight in a hydro-monoplane.

Gertrude Bacon described her experiences:-

In an article in The Aeroplane Magazine, 1 August 1912 ‘The glorious upper reaches of the lake, with its surrounding mountains, opened out in matchless panorama, and the wide, practically empty water stretched for miles and miles ahead. Truly this beats every other flying-ground’.

In her book Memories of Land and Sky ‘To fly over water is certainly to taste to the full the joy of flight, and when the water is Windermere and the scenery the pick of English Lakeland, which is to many a traveller the pick of the whole world, in its soft intimate loveliness, the result is something not lightly forgotten’.

PROTESTS

Protests took place against flying at Windermere

A Committee was established; the principal spokesperson for the objectors being Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley.

On 8 January 1912, Wakefield wrote to the Royal Aero Club (‘RAeC’) requesting the RAeC to use its influence to prevent any Order under the Aerial Navigation Act 1911 prohibiting flights over Windermere. The RAeC resolved to send a copy to the Secretary of State expressing the hope that no Order would be made. Correspondence was also received by the RAeC from the Protest Committee.

On 14 January 1912, a Circular was issued from the Windermere Hydro-aeroplane Protest Committee to the Ratepayers of the Windermere Urban District. Wakefield wrote his comments on this print. He compiled a Circular in reply.

Opinion was divided: for example, the Westmorland Gazette of 20 January 1912 carried not only a letter from Beatrix Potter that any increased numbers of trippers being attracted to Bowness due to hydro-aeroplanes would not be sustained, but also a report of a meeting convened by the Windermere Trades Association on 16 January at St. John’s Parish Room which supported them as an advantage to the district.

On 24 January, a Ratepayers’ Meeting at Bowness Institute with a full attendance, passed a resolution with a large majority in favour of aeroplane development. – Manchester Guardian, 25 January 1912. It was ‘one of the largest meetings of recent years’. – The Lakes Herald, 26 January 1912.

There was a national campaign, deputations were made to the House of Commons, and many letters were written by both sides including to Windermere Urban District Council, Westmorland Council, Westmorland Gazette, The Times, Globe, Liverpool Daily Courier, Daily News, Yorkshire Post, Country Life, Spectator, Aero magazine and Flight magazine. The Royal Aero Club appointed a Sub-committee and invited Wakefield to state his views.

As an example exchange to The Times, Rawnsley’s letter was replied to by Wakefield which included that he did not permit flights on Sundays.

To the suggestions that tests should take place upon the sea, Wakefield’s stance was that Windermere, being the largest stretch of water in England, was the best for experimental purposes in the whole country. He pointed out the obvious risk which he would undergo in the early stages of his experiments were they to take place on the sea.

However, Wakefield was initially unable to cite his Admiralty contract since he had signed an assurance that he would comply with the Official Secrets Act.

In an interview with Robert Loraine ‘the Famous Actor-Aviator’ published in the Manchester Dispatch of 23 January 1912, he compared Windermere with Lake Como and Lake Lugano and pointed out that there had been no protest recorded against aircraft there.

Humphrey Verdon Roe replied to Canon Rawnsley by way of another interview reported 3 days later in the Manchester Dispatch. “British aviators, naturally desiring that this country shall keep abreast of foreign nations in developing the science of flying, keenly regret such campaigns as this. … The direct hampering of important experiments like those of Mr. Wakefield is too bad.”

The Westmorland Gazette of 3 February 1912 carried an item which reported as to proposed high spend by France on experiments in connection with naval aeroplanes, whilst there was an agitation against the privately financed experiments on Windermere. ‘We dare venture the opinion that were Windermere in France not only would there be no agitation, but that money, both public and private, would be offered freely for the helping forward of serious and useful experiment.’

Everything hung in the balance on 16 April 1912

Upon a question being raised in the House of Commons, the answer as to the government’s position came from Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. He declared that flying would continue at Windermere.

A Public Inquiry took place on 27 August 1912 as to navigation and speed on or above the lake

Issues did not end with Churchill’s declaration in the Commons, in that on 24 June 1912 Windermere Urban District Council petitioned the Board of Trade for an additional rule to be made that no vessel (it was common ground that this would not include the Furness Railway Company’s steamers) should navigate certain portions of the lake at a greater speed than 12 mph. The significance was that, in order to take off, a hydro-aeroplane ordinarily needed to achieve 30 to 35 mph.

As recorded in the Council’s Minutes of 22 July 1912, Wakefield had applied to the Council for a copy of its Petition. He had compiled a response on behalf of the Lakes Flying Company, and, on 6 July 1912, wrote the Board of Trade requesting to be heard.

The Inquiry’s remit was to advise the Home Office and the Board of Trade as to whether firstly any additional Rules should be added beyond Article 22 of the Rules made under the Merchant Shipping Act, 1894 by Order in Council of 19 November 1902 for navigation on Windermere, which Article imposed a 6 mph limit for the portion of the lake opposite Bowness known as ‘the Narrows’, and secondly any action should be taken under the Aerial Navigation Act, 1911 [which gave power to the government to prohibit flying over prescribed areas]. Wakefield had no objection to the speed in this portion being increased to 12 mph, but took issue as to it being extended over considerable areas of the lake.

Allegations against hydro-aeroplanes resulted in this remarkable exchange!

Nothing as to the outcome of the Inquiry appeared in the Minutes of the Council or the RAeC. It is therefore presumed that the outcome was that no Order was made under the Aerial Navigation Act, or otherwise.

A Public Inquiry took place from 10 May 1994 for 13 weeks as to imposing a byelaw for a speed limit of 10 mph

The Lake District National Park Authority (‘LDNPA’) applied for a Judicial Review of the rejection of such a byelaw by the Inquiry, which application was not contested by the Government.

New Byelaws therefore came into effect on 29 March 2000 for 10 mph, but implementation was delayed for 5 years to allow time for businesses to adapt.

The Windermere Navigation Byelaws 2008, made under section 13 of the Countryside Act, 1968, consolidated the existing byelaws including a 6 mph limit within 4 specified areas. There is otherwise a 10 knots per hour limit, following re-submission by LDNPA and confirmation on 13 September 2012 by the Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (‘DEFRA’) of the Byelaws due to inconsistency with the Inquiry’s outcome at 10 miles per hour. So, Windermere has a marginally higher speed limit of 10 nmph than Ullswater, Derwentwater and Coniston Water at 10 mph.

Further, the above re-submission resulted in confirmation by DEFRA that LDNPA has power to grant permission to exceed the speed limit on Windermere by way of an exemption application process. The Lake District Coniston Water Byelaws 2020 also include a speed limit exemption process.

PIONEERING THE USE OF WIRELESS

In putting forward the hydro-aeroplane for a role of scouting, Wakefield envisaged the relaying back of information to be achieved by a wireless installation. On 19 July 1912, an Admiralty representative came to Windermere so as to observe a new method of transmitting wireless messages from Waterhen. In March 1913, The Lakes Flying Company was issued with a licence by the General Post Office for experiments in wireless telegraphy.

For details of cover, please click here. Bray, Gibbs & Co Ltd had ’90 per cent of the trade’. – The Aeroplane magazine, 17 October 1912. Third Party cover then had a limit of £1,000, to be contrasted with the amount today for the replica Waterbird at £1,750,000.

TEACHING PILOTS

The first civilian Seaplane School was established. The initial lesson was given on 9 September 1912 to Second Lieutenant John Trotter. On 12 November 1912, Trotter was awarded Aviator’s Certificate No. 360, the first UK Certificate with the tests having been achieved on a hydro-aeroplane.

Lessons included flying by moonlight, ‘a feature unique to this special school’. – Flight magazine, 5 February 1915.

Wakefield was proactive as to Aviators’ Certificates, writing the RAeC and accompanying its delegates to a Conference at Paris on 28 January 1913, when the rules were drawn up by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale for Hydro-aeroplane Certificates. The first 2 such UK Certificates were awarded to Windermere pupils Joseph Bland on 30 August 1913 and Oswald Lancaster on 15 April 1914.

REMARKABLE EXPERIENCES

Second Lieutenant John Trotter

The Westmorland Gazette, 12 July 1913:

‘Lieut. Trotter had Mr. Gnosspelius’s monoplane out on Monday. He made two flights upon it, and in concluding a third he descended in Parsonage Bay. By some mischance the machine instead of alighting horizontally, or nearly so, on the surface of the lake dipped into the water with its front end and turned right over from back to front. The propeller was broken, this being about 200 yards from the shore; but he seized hold of the upturned hydro-aeroplane and was soon taken off by a motor-boat which was approaching. He received a cut on the chin but was otherwise unhurt, and later in the evening the hydro-aeroplane was righted and towed to the shed at Bowness for repairs. Lieut Trotter, seeing what was going to happen, jumped from a height of 12 or 15 feet into the water in order to avoid risk of injury from becoming entangled in the machine.’

Flight Lieutenant John Cripps

Trotter was not the only pilot associated with Windermere to jump from an aeroplane to save himself. As described in The Story of a North Sea Air Station by C F Snowden Gamble. Flight Lieutenant John Cripps (later Flight Commander), who commanded Royal Naval Air Station Windermere from May 1916 until January 1917, and was previously the Senior Flying Officer at RNAS Great Yarmouth, was endeavouring to locate approaching airships north of the town when the engine of his B.E.2c stopped.

The Daily Report, 9 September 1915:

‘Owing to complete darkness and mist on the ground, the pilot could see nothing but blackness underneath him, and as he was afraid of his bombs going off if he hit a house or a wall, he landed in the following manner. When his altimeter showed 100 feet he stepped out on to the planes, still holding his control lever. He held the machine down for about 6 seconds and then jumped off the machine, and he fell on his shoulder on some soft mud and was unhurt. The machine landed by itself and sustained very little damage.

‘One of Cripps’ brother officers remarked at the time that ‘He was absolutely scared stiff – not by his landing, for he wasn’t scratched – but by the cows that came up and smelt him and his machine.’

HORNSEA HORSE SHOW

Save for Avro 504s to Douglas, Isle of Man and on charters flown in 1919 by Pixton, there was only one occasion when a Windermere-based aeroplane flew out of the Lake District. That is, having arrived by traction engine of J. Wharton & Son on 11 June 1913, Waterhen [Note the wheels in this photo] was exhibited on land and flew the following day from Hornsea Mere, Yorkshire (which later became a Royal Naval Air Station). The first passenger was Stanley Wilson, MP for Holderness.

There was a delay in the outward journey of 5 hours caused by the traction engine breaking down at Kirkby Lonsdale, where it remained in the middle of the road whilst the steering was repaired. Whartons traded from 18 Market Place, Kendal and the station yard, with depots at Beezon Road and Maude Street.

Wakefield re-joined the army, and, on 11 November 1914, the Cockshott hangar lease, an option on the hangars at Hill of Oaks, together with Waterhen, Seabird and the Lakes Monoplane plus ancillary equipment were sold for £2,550 to the Northern Aircraft Company Ltd. In 1916, a double-bay hangar was added at Hill of Oaks.

Upon Adams taking up a commission with the Royal Naval Air Service, his successor was Rowland Ding. Ding became a director, general manager and chief pilot of the Northern Aircraft Company Ltd, whose booklet About the Seaplane School, by Clifford Fleming-Williams, included that he was ‘the first aviator to carry a member of any Royal Family as a passenger’: Princess Anne of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg, from Hendon to Calais on 21 May 1914. The Company ceased trading in August 1916.

Waterhen was the longest-serving of all the Windermere seaplanes, from 30 April 1912 until 16 August 1916.

The Seaplane School was requisitioned and became a Royal Naval Air Station during 1916-17. Large numbers of Flight Sub-Lieutenants were sent to Windermere, who held the rank of probationer and were appointed to HMS President II (Crystal Palace, London), where they had previously undergone an intensive 5-week course in drill, navigation, theory of flight, aero-engines and signalling. Failure at Windermere could result in withdrawal of their rank. Not all pupils finished their course of flying instruction at Windermere, and completed the tests for their Certificates elsewhere.

On 19 July 1916, the Station was honoured with an inspection by the First Sea Lord (later Admiral of the Fleet) Sir Henry Jackson.

However, Wakefield was not paid for use of his land by the Admiralty, but, after instituting court proceedings, he received £90 plus 6 porcelain baths and a kitchen range!

TRANSPORTATION

Aeroplanes were delivered to Windermere station and onwards by road, or to Lakeside station and onwards by water

Waterbird arrived from Brooklands on 7 July 1911. On 5 June 1912, a Borwick & Sons’ pile driving barge was used from Lakeside for the Deperdussin aeroplane – this article is from The Daily Sketch, 8 June 1912. In April 1916, an F.B.A. flying boat and Nieuport seaplanes were hauled by rail, and then respectively by RNAS tender and steam lorry to Hill of Oaks. Also, in January 1917, a Short 827 was sent from Windermere by rail to the School of Aerial Gunnery at Loch Doon, near Ayr.

Delivery of materials

Delivery of petrol and oil was by horse and cart.

Delivery of Waterhen from Windermere

Wakefield wrote offering for Waterhen to be exhibited at the world’s first seaplane meeting in March 1912 at Monaco, but withdrew his offer. Delivery took place to Hornsea in June 1913, as mentioned above.

Equipment at the Seaplane School

A 40hp car, a fast motor launch and a 40 knot hydroplane which was used to give students practice in travelling fast over water, judging speeds and also as a safety attendant.

Personal transport

Pilots invariably rode motorcycles. ‘Aviators, especially in the fledgling stage, are not down-hearted as a rule; in fact they are usually a lot of harum-scarum young devils, much addicted to high-spirits and high-powered motorcycles. They live, move, and have their being in oil-besmeared clothes, astride of something over 7 horse-power’. – An article on training pilots at Windermere by Fleming-Williams in The Royal Magazine, January 1916.

SUBSEQUENT APPOINTMENTS OF WINDERMERE PILOTS

Chief Test Pilot

Ding for the Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Company Ltd.

Ralph Lashmar for White Aircraft.

John Lankester Parker for Short Brothers, who test-flew the first Windermere-assembled Sunderland flying boat in 1942.

Whilst Adams was not an employee of Avro, his achievements at Windermere and elsewhere were such as to warrant inclusion as a Chief Test Pilot by Peter V Clegg in his book Avro Test-Pilots since 1907.

Also, Gnosspelius took charge of Short Brothers’ experimental department and flew on many test flights.

Marshal of the RAF

The highest rank achieved by a Windermere-trained pilot was Marshal of the RAF

Flight Sub-Lieutenant William Dickson, who began his training at Windermere on 11 November 1916, rose to Marshal of the RAF Sir, GCB KCB CB KBE CBE OBE DSO AFC. On 19 July 1918, he took part in the first aircraft carrier-borne strike, when 7 Sopwith Camels from HMS Furious attacked the airship sheds at Tondern.

CAPTAIN HOWARD PIXTON

On 21 July 1919, Pixton flew an Avro 504K to Windermere, with another 1 week later, operated by The Avro Transport Company. Based at Cockshott until 8 October, services included joyriding, instruction, delivering newspapers to the Isle of Man and also carrying passengers to and from the island. ‘30,000 Daily News were delivered daily, by using a special compartment instead of the usual passenger accommodation.’ – Flight magazine, 14 August 1919.

WORLD WAR 2

Sunderland Flying Boat Factory

Between September 1942 and May 1944, 35 Short Sunderland flying boats were assembled at White Cross Bay, plus 25 were then refurbished.

More information is at Articles 3 and 4 here.

During 1944 and 1945, 3 Catalina flying boats landed on the lake.

A modified Slingsby Falcon 1 glider was flown from the lake on 3 February 1943 by Flight Lieutenant Cooper Pattinson and on 7 February by Flight Lieutenant Wavell Wakefield.

On 7 February 1973, a first day cover was issued.

Women’s Auxiliary Air Force Officers

Pixton had won the Schneider Trophy for a seaplane contest in 1914 at Monte Carlo. The Trophy was presented by Jacques Schneider, who shared the same great-grandfather as Henry Schneider, a Barrow-in-Furness industrialist who from 1869 until 1887 lived at Belsfield (a Hotel since 1892), Bowness-on-Windermere. The Hotel was requisitioned for training WAAF officers, whose varied duties included: Accounts, Air Raid Warning, Catering, Code and Cypher, Equipment, Filter [processing radar information], Intelligence, Ops ‘B’ [scrambling pilots into action], Photographic Interpretation, Radar, RAF Administration, Signals, and Torpedo Assessment.

AERONAUTICAL FEATURES IN BOATS AT WINDERMERE

1917 Rolls-Royce Hawk Mk. 1. From Royal Naval Air Service airship Submarine Scout Twin S.S.T.3. In Canfly, which was built in 1922 to receive the engine. A starting magneto and primer from a Rolls-Royce Eagle engine were fitted.

Napier Lion VIIB. In each of Estelle I and Estelle II in 1928, driven by Betty Carstairs. Of the type which powered the 1927 Schneider Trophy-winning Supermarine S.5 seaplane.

Rolls-Royce R. Twin engines in Miss England II in 1930, driven by Sir Henry Segrave. Built by Saunders-Roe Ltd. Of the type which powered the 1929 Schneider Trophy-winning Supermarine S.6.

White Lady II. Raced at Windermere during 1936-1937, driven by Derek Tinker. ‘The sole survivor of her particular generation of speedboats on Windermere, providing the link between the earlier displacement boats such as Canfly and the later Chris-Crafts introduced before the Second World War.’ – Booklet on her salvage and restoration produced by Windermere Nautical Trust Ltd. Built in 1930-1931 by the British Power Boat Co Ltd; which also built Miss England I, the first speedboat used by Segrave. A hydroplane, with a stepped hull. The decks and cowls are covered with aeroplane fabric for lightness. The designer was Hubert Scott-Paine. In 1916, Scott-Paine bought Pemberton-Billing Ltd and renamed it Supermarine Aviation Co Ltd, which he sold in 1923. In 1922, the Supermarine entry regained the Schneider Trophy. In 1927, he purchased the Hythe Shipyard, renaming it the British Power Boat Co Ltd.

SEAPLANES WHICH FLEW AT WINDERMERE

Between 1911 and 1919

Waterbird, Gnosspelius No. 2, Waterhen, Deperdussin, Avro Duigan/Seabird, Gnosspelius-Trotter, Lakes Monoplane, Blériot XI, Blackburn Improved Type 1, Fleming-Williams P.B.1, Nieuport VI.Hs, F.B.A.Type As, Short 827s and Avro 504Ks.

From 1920

Supermarine Southampton (1931), Saunders-Roe A.19 Cloud (1933), Short Sunderland flying boats (1942-1945 and 1990), Slingsby Falcon 1 glider (1943), Consolidated Catalina flying boats (1944-1945 and 1994), Short Shetland prototype (1945), de Havilland Tiger Moth (1979), Cessna 180 (1983), replica Waterbird (2022-2024), 2 Aviat Huskies (2023) and Aviat Husky (2024).